Tony Dreise asks – What is the role for teachers in improving school attendance among Indigenous children and young people?

Recently I co-authored a paper on Indigenous school attendance. In our paper, we found that school attendance among Indigenous children and young people has been improving over recent decades and years.

There is still a way to go – latest data indicate a 10 per cent attendance gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous students. In some parts of Australia, it is much larger at near 30 per cent. We found that regular school attendance is particularly challenging for Indigenous students in remote areas and in secondary schooling.

To turn this around, we argue that expectations need to be ‘really high' and ‘highly real'. By that we mean: '…‘really high' expectations of schools, students and parents and carers, and ‘highly real' expectations about the social and economic policies and environments that stymie educational success.'

Educational research throughout the world points to the importance of school cultures that are driven by ‘high expectations' of teachers and students alike. Within these school cultures, principals are leading, teachers are teaching smart and students are working hard.

A 'catch 22' dilemma

Our paper also contends that the relationship between education and wellbeing is akin to a ‘catch 22' dilemma. That is, we know that education is key to turning around current levels of Indigenous socioeconomic disadvantage. In other words, education is an investment not a cost.

In a paper called Education and Indigenous Wellbeing (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2011), the ABS presents a compelling relationship between education and social wellbeing among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. In addition to improving employment prospects, ABS data show that Indigenous people with education qualifications are more likely to own a home or be paying off a mortgage, less likely to live in overcrowded housing, less likely to be arrested, less likely to smoke or misuse alcohol, and more likely to enjoy greater overall wellbeing.

We also know that the current state of poverty and dysfunction that communities find themselves in adversely impacts on young people's academic growth. Children find it hard to learn on empty stomachs for example. Teenagers will find it difficult to attend school if they're being bullied at school because of their race. Hence the 'catch 22' dilemma.

So how do we turn around rates of school attendance in locations where it is poor? And more specifically, what can teachers do?

Demand and supply

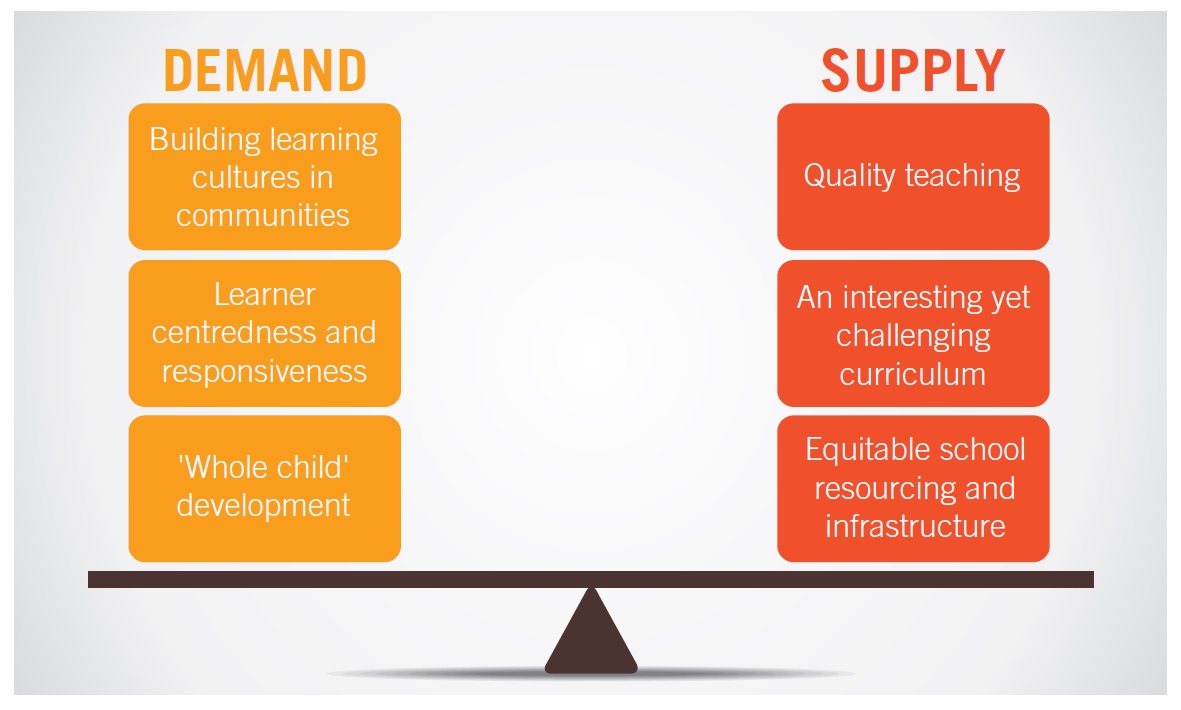

In our paper, we present the following diagram which represents the need for balance between ‘demand' and ‘supply' factors in education:

[Graphic from 'Indigenous school attendance: Creating expectations that are ‘really high' and ‘highly real']

In fashioning responses to current educational inequities, school systems and policymakers tend to favour ‘supply' side levers such as spending more on professional development among teachers, or employing more Indigenous education assistants, or allocating more to information technology. These are all important, but we cannot afford to overlook the equally important job of attending to the demand side of the education. That is, investing in communities to foster a love of lifelong learning and demand for quality teaching and learner responsiveness. It also means that teachers and schools are delivering quality teaching through culturally-customised, learner-centred and strengths-based approaches. It also means fostering bonds and affinity between teachers and students. Relationships of trust are of paramount importance.

You will also note the reference to ‘whole child development' in the model. By this we mean that children need to grow not only academically but emotionally, socially, physiologically, and culturally. Strong relationships between schools, families, and community agencies (in health, children's services, etc.) are therefore critically important. In order for children to learn, they need to be safe, nourished, stimulated, engaged, and ideally confident.

What can teachers do?

Teachers can do a number of practical things to meet the needs of the ‘whole child'. One is the delivery of a full and rich curriculum, whereby learners are engaging in literacy and numeracy, bi-cultural and social growth, music, arts, science, and physical education. Where the purpose and objectives of lessons are clearly understood by learners, and the methods of teaching are energetic and diverse – from teacher-led, to peer-led, to project-driven, to ICT-based, and community- (excursion) based; depending upon what needs to be learnt.

Second, creating school cultures whereby Indigenous cultures and peoples are respected, by consistently engaging the families of learners, not just during NAIDOC week. Where teachers and school leaders are fostering genuine interest in the child's life, be it their sporting life, their cultural life, their social and family life. Third, by searching and building upon learners' strengths. Fourth, by adopting ‘growth mindsets', so that teaching is constantly oriented toward personal improvement, daily, weekly, yearly – which means assessing for growth that goes beyond mere ‘pass/fail' thinking.

Teachers can also work with their school and community leaders in bringing about initiatives that actively tackle forces that stymie student flourishing. The little things can make a big difference. For example, Brekkie Clubs can literally provide food for thought. Storing spare stationery and school uniforms in a cupboard can help overcome a sense of shame among students whose family circumstances may be rocky.

School leaders and teachers can foster a culture of ‘school matters' by data collecting, rewarding regular attendance and building bridges between homes and school. Schools can also think of themselves as ‘hubs' for child development and growth, by integrating children's academic growth with their health, wellbeing and safety by working with government and community non-government agencies.

Finally, school and community leaders can work together to ensure that Indigenous learners gain access to the services that they require, be it speech pathology, psychological counselling, literacy and numeracy coaching, or culturally affirming student support services.

To read the full Policy Insights paper – Indigenous school attendance: Creating expectations that are ‘really high' and ‘highly real' – by Tony Dreise, Gina Milgate, Bill Perrett and Troy Meston, click on the link.

References

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2011). Education and Indigenous Wellbeing (4102.0). Retrieved from www.abs.gov.au

Related ACER content: Research Developments – Boosting Indigenous school attendance