Over the past several decades, psychologists have identified the importance of meeting three core psychological needs for optimal human functioning: the need for autonomy, the need for competence, and the need for belonging (Ryan & Deci, 2017).

Autonomy is the feeling that we are the driver of our own actions. Competence is the perception that we are effective in the tasks we undertake. Belonging is the feeling that we are cared for and connected to important others.

In the academic domain, when all three psychological needs are met, students tend to be more engaged in their schoolwork. However, there are many students whose psychological needs are not met (Chen et al., 2015). Some, in fact, experience the opposite – they feel a lack of autonomy, competence, and belonging. This is known as psychological need frustration. What happens when this occurs?

In a recent study, we examined the role that psychological need frustration plays in students' engagement in school (Collie, Granziera, & Martin, 2019).

What is psychological need frustration and why is it important?

A lack of autonomy (or, feeling excessive pressure) occurs when students feel that they are overly controlled by others and have no say about, or input into, what they do at school or in their schoolwork.

Incompetence occurs when students do not feel capable and lack confidence in their abilities at school.

Finally, loneliness occurs when students feel excluded and lack a sense of belonging with important others at school, like their peers and teachers.

Taken together, psychological need frustration means that students are not faring well at school. For example, researchers have shown that loneliness at school is linked with lower mental health (Løhre, Lydersen, & Vatten, 2010).

It is therefore important to help students avoid feelings of pressure, incompetence, and loneliness. In fact, recent research has shown that when students experience less psychological need frustration, they are more motivated for their schoolwork (Bartholomew et al., 2018).

In our study, we wanted to test whether psychological need frustration is also linked with students' engagement at school. In particular, we focused on two problematic forms of engagement: disengagement and self-sabotage.

What are disengagement and self-sabotage?

Engagement can be adaptive – such as persisting on a task even when it becomes difficult. However, it can also be maladaptive – which involves students undertaking actions that actually get in the way of their efforts and performance at school.

We examined two forms of maladaptive engagement: disengagement and self-sabotage.

Disengagement occurs when students have largely given up on school. They invest very little effort in their schoolwork, and sometimes none at all. Self-sabotage happens when students engage in behaviours like procrastination so they can use this as an excuse if they do not perform well.

Together, disengagement and self-sabotage are types of problematic behaviours that we want to reduce among students. To do this, it is important to discover what factors predict the two behaviours.

What did we examine?

We asked 771 Australian secondary school students to rate their psychological need frustration, their disengagement, and self-sabotage via on online survey.

For example, we asked students about their psychological need frustration with items like, 'I have doubts about whether I can do things well at school'. For disengagement, we included items such as, ‘Each week I'm trying less and less'. For self-sabotage, students answered items such as, 'I sometimes don't try hard at assignments so I have an excuse if I don't do so well'. Students rated each item on a 7-point scale from ‘strongly agree' to ‘strongly disagree'.

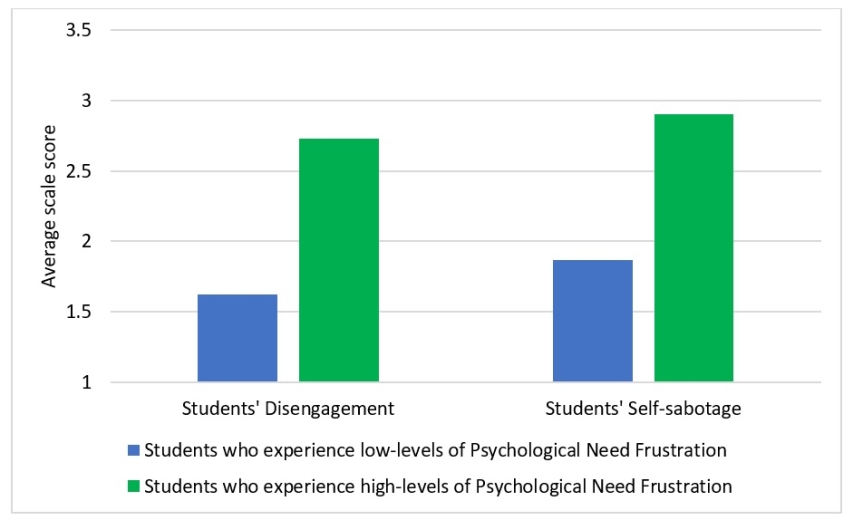

Our results showed that when students felt less pressure, incompetence, and loneliness at school, they also reported being less disengaged from school and using fewer self-sabotaging strategies. Lower psychological need frustration, then, was associated with fewer problematic engagement behaviours among students.

Investigating the link with teachers' motivational practices

Knowing this, we suggest it is important to look at factors that may play a role in helping to reduce students' psychological need frustration. One relevant factor involves the interactions that students have with their teachers in the classroom. In particular, we were interested in the practices that teachers can use to reduce students' psychological need frustration.

Therefore, in our study, we also asked students about their teachers' motivational practices in the same survey.

Our results showed that when students felt their teachers used fewer psychologically controlling practices, they also reported less psychological need frustration. Psychologically controlling teaching practices involve motivating students by activating anxiety, guilt, and shame. For example, these practices can include expressing disappointment about students' performance or withdrawing attention or support when students do not do as well as expected on a task.

Implications for classroom practice

Given these findings, teaching practices might therefore be one way to help reduce students' feelings of psychological need frustration. For example, teachers might want to avoid practices that pressure students to act and feel certain ways — and instead, incorporate students' own perspectives into class activities and help students to be more self-directed at key points in the learning process. Teachers might also want to avoid practices that motivate students through guilt or shame, and instead motivate with encouragement and emotional support.

In fact, our results also showed that students reported less disengagement when they felt their teachers used more supportive practices. Supportive practices involve teachers motivating students with encouragement and emotional support, and allowing students opportunities for self-initiative in what they do at school.

Conclusion

Adolescent students' psychological experiences in the classroom matter for their engagement at school. In particular, when students experience less pressure, incompetence, and loneliness at school, they also report lower disengagement and self-sabotage. Notably, teachers appear to have an important role to play in reducing students' psychological need frustration and problematic engagement.

References

Bartholomew, K. J., Ntoumanis, N., Mouratidis, A., Katartzi, E., Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C., & Vlachopoulos, S. (2018). Beware of your teaching style: A school year-long investigation of controlling teaching and student motivational experiences. Learning and Instruction, 53, 50-63.

Chen, B., Vansteenkiste, M., Beyers, W., Boone, L., Deci, E., Van, d. K., . . . Verstuyf, J. (2015). Basic psychological need satisfaction, need frustration, and need strength across four cultures. Motivation and Emotion, 39(2), 216-236.

Collie, R. J., Granziera, H., & Martin, A. J. (2019). Teachers' motivational approach: Links with students' basic psychological need frustration, maladaptive engagement, and academic outcomes. Teaching and Teacher Education, 86, 102872.

Løhre, A., Lydersen, S. & Vatten, L.J. (2010). Factors associated with internalizing or somatic symptoms in a cross-sectional study of school children in grades 1-10. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 4(1), 33.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

The authors suggest teachers avoid practices that motivate students through guilt, or shame. Think about your own classroom practice: What strategies do you use to motivate students? How do you react when students don’t do as well as they are expected to on a task? How do you ensure students’ own perspectives form a part of classroom activities?