Is ATAR necessary?

The Australian Tertiary Admissions Rank (ATAR) dominates senior secondary schooling in Australia. For many parents and students, it is the principal measure of 13 years of learning and the key indicator of a student’s academic performance and future potential. It takes precedence over information provided on senior school certificates; drives a wedge between ATAR and non-ATAR studies in the senior years; differentially values university courses according to their ATAR cut-offs; and is used by schools in their marketing campaigns and by the media for comparing schools. And yet, it was not designed for any of these purposes.

I believe we could dispense with ATAR at almost no cost, but significant benefit. There are several observations that lead me to this conclusion.

First, it is regularly claimed that ATAR is the best available predictor of university success. In reality, the best available predictor of how students perform at university is how they performed at school. ATAR is based entirely on students’ scaled subject scores and so adds nothing to prediction beyond the information in those scores. It is scaled subject scores that are the best currently known predictor of university success.

ATAR is one way of conveying the information in those scores. But it is not the only way. And it may not be the best way from a predictive point of view. For example, while it is not being proposed here, differentially weighted scaled subject scores may be a better predictor of university success than ATAR.

This is an important observation, because it identifies ATAR merely as a carrier of the information essential to current university selection processes. I believe the construction of ATAR could be bypassed with few, if any, adverse consequences for student selection.

Second, and contrary to popular belief, ATAR is often not the index on which students are ranked for selection into university courses. For example, in New South Wales, students are ranked and selected on the basis of an index known as the course ‘Selection Rank’. This rank is calculated for each university course separately. It includes ATAR but also can include other evidence at the discretion of individual universities and courses (referred to in NSW as ‘adjustment factors’). As a result, what determines whether a student is admitted to a course is their position on the course Selection Rank, which is often different from their ranking on ATAR.

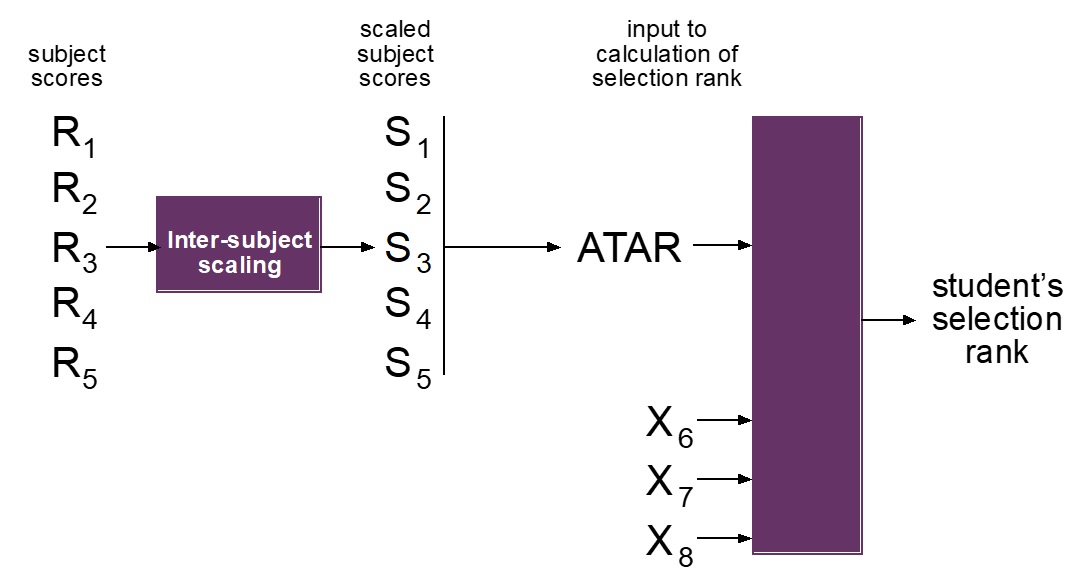

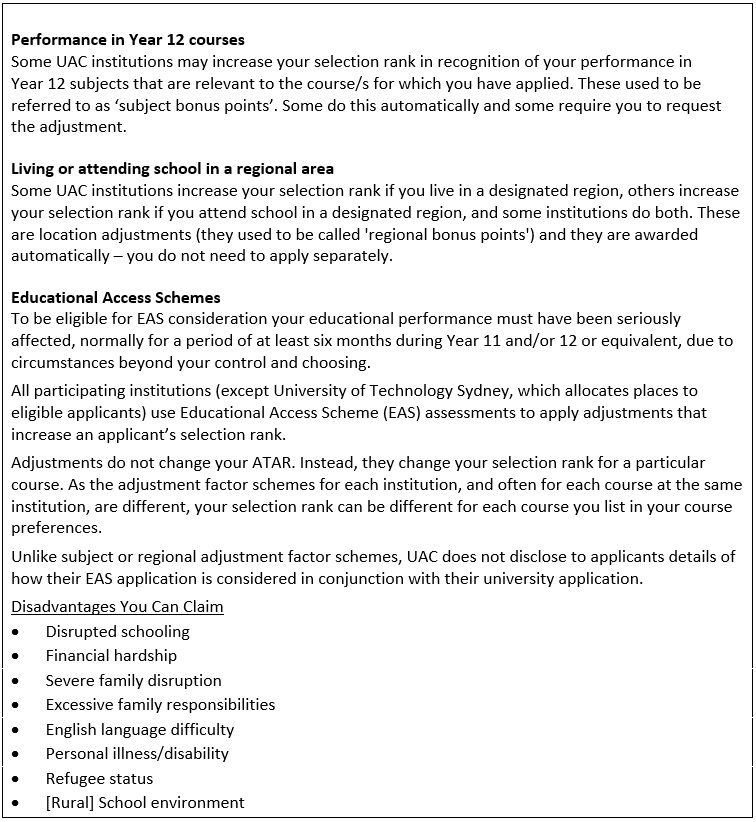

Figure 1 illustrates this. Each student’s subject scores (R) in the NSW Higher School Certificate are converted to scaled scores (S) as a result of an inter-subject scaling process. These scaled scores determine the student’s ATAR. The process of arriving at the student’s Selection Rank for a given course uses ATAR, but may also use other available information (X). The Universities Admissions Centre (UAC) – which processes applications for admission to tertiary courses mainly in NSW and the ACT – explains this as Selection Rank=ATAR+Adjustments [1]. In recent years, there has been an increase in the use of other information in the calculation of course Selection Ranks. A UAC list of possible adjustments is shown in the breakout box at the foot of this article. Individual institutions have their own adjustment schemes, such as the University of New South Wales adjustments for Elite Athletes, Performers and Leaders (adjustments for Duke of Edinburgh Awards, debating, chess, music, and so on). [2]

Figure 1. Current NSW process for determining a student’s course Selection Rank

Figure 1 makes clear that ATAR carries the information in scaled subject scores into the process for constructing what ultimately matters – the course Selection Rank. In this sense, it is an intermediate step in the overall process. And, given that ATAR adds nothing over and above the information in scaled subject scores, its separate reporting could be removed, as shown in Figure 2.

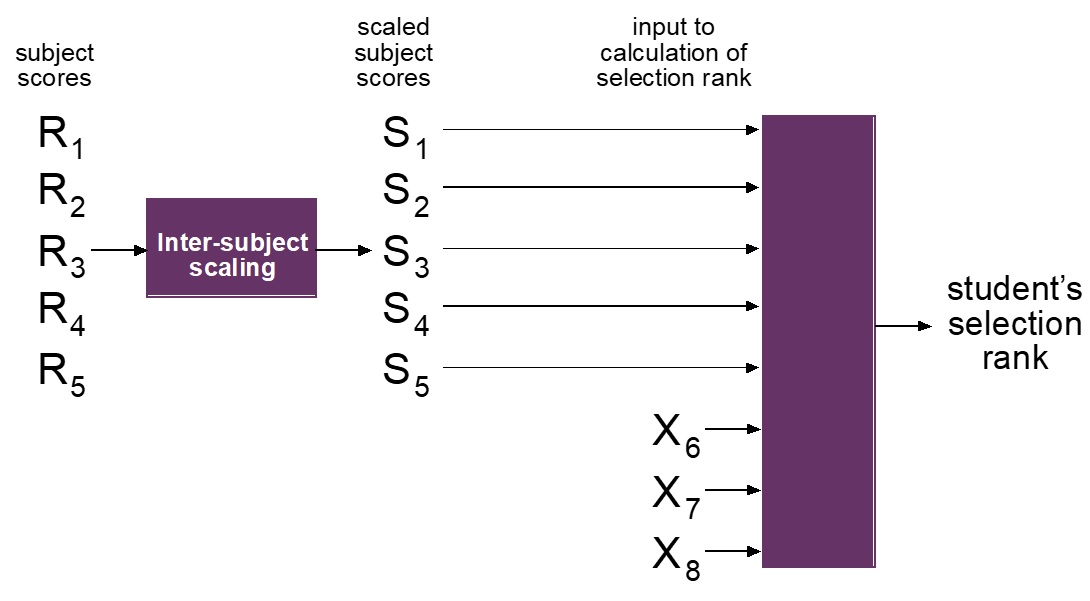

Figure 2. Possible process for determining a student’s course Selection Rank

In Figure 2, scaled subject scores are input directly to the process for constructing the course Selection Rank, along with any other nominated evidence (X). This process for constructing the course selection rank could be identical to the current process, meaning no change to a student’s selection rank or to universities’ selection decisions. The difference would be that ATAR would not be reported.

Third, the original purpose of ATAR was to provide a single rank order of all ATAR-eligible school leavers, regardless of the university or course to which they were applying. However, given the increasing use of supplementary evidence in ranking students for entry to particular courses, and variations in the nature and weighting of that evidence from one institution and course to another, it is not obvious why every school leaver now needs to be placed in a single queue. There are now multiple entry points and pathways into universities and different rankings of applicants for different purposes. The attempt to line up all students as though they were entering through the same door seems increasingly irrelevant.

Fourth, it is sometimes believed that ATAR provides a level of transparency in student selection and that assigning every student an ATAR is in some way ‘equitable’. However, to the extent that other information is used in the construction of course Selection Ranks, transparency depends on knowing what other information is used and how it is used. Transparency and equity are not guaranteed by assigning everybody an ATAR, but by making clear what other evidence is used to construct course Selection Ranks and by ensuring that this evidence is fair to all applicants.

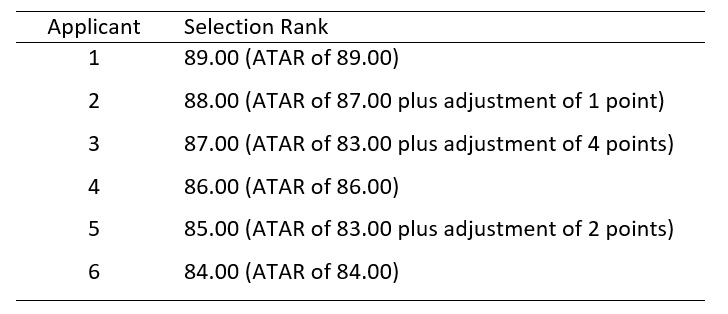

An example provided by the UAC on its website illustrates that ATAR alone can be insufficient for understanding selection decisions. The UAC example is based on a hypothetical course with three available places, but six applicants:

It is accompanied by the following explanation:

Offers will be made to applicants 1, 2 and 3. Applicant 4 won’t receive an offer, even with an ATAR higher than applicant 3, and applicant 3 will receive an offer even though their ATAR is below the lowest selection rank… The example also shows that an applicant with an ATAR above the published lowest ATAR for a course will not necessarily receive an offer.

This example reinforces the point that it is not ATAR but the course Selection Rank on which applicants are ranked and that determines a student’s successful selection into a course.

Fifth, ATAR is sometimes considered important because of the role it plays in students’ decisions to change course preferences. Once students receive their ATAR, they are able to compare it with the previous year’s course Selection Rank cut-offs. They then have a window of time in which they can change their preferences. (UAC’s advice is to ‘Remember that selection ranks include adjustment factors. The selection rank is not necessarily the ATAR you need to get an offer.’)

An alternative, and perhaps more transparent, approach would be to tell applicants directly how many places are available in each of the courses to which they have applied, and where they stand in the current ranking of applicants to that course (for example, ‘18 places available and you are currently ranked 16th’). Students could then decide whether to change their course preferences without reference to ATAR, adjustment factors or course Selection Ranks.

In summary

ATAR was designed to provide a single ranking of all university applicants. However, ATAR now dominates the senior secondary school, over-prioritises selection into university as the purpose of this phase of schooling, and has a range of other unintended and unhelpful uses and consequences. For these reasons alone, it should be reconsidered. The case for change is even stronger when it is recognised that universities’ growing use of other information in their selection processes makes a single rank order of all university applicants largely redundant; for students, course-specific rankings rather than ranking by ATAR are increasingly what matters.

However, abolishing ATAR would require a replacement. The replacement proposed here is a student’s position in the ranking of applicants for each course, together with the number of places available. When accompanied by the information already provided to students (their Year 12 subject results and details of any other information used in determining their ranking for a course), this replacement would be at least as transparent as ATAR, with fewer downsides.

Explanation for students of possible adjustment factors in calculating selection ranks [3]

[1] https://www.uac.edu.au/future-applicants/admission-criteria/university-selection-rank-adjustments

[2] https://www.futurestudents.unsw.edu.au/adjustment-factors-eapl

[3] Excerpts from UAC website: https://www.uac.edu.au/future-applicants/scholarships-and-schemes/educational-access-schemes (accessed 24 May, 2020)