How do Australian students see their teachers?

In a year that has seen a great deal of disruption to classes, the relationship between students and their teachers has become far more important. A new national report on the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) gives us some insights into this relationship, as most students that were surveyed for PISA 2018 are in the final years of their secondary schooling in 2020.

In particular, student perceptions of the level of support and the quality of feedback they received from their teachers at that point of time might well have an influence on how students adapt to the current learning environment.

Teacher support

The teacher-student relationship plays an important part in creating a positive learning environment. When teachers show care and concern for their students, it is more likely that their students will likewise show care and concern in a manner that is reflected in a supportive classroom environment (Lei et al., 2018; Klem & Connell, 2004).

Support from teachers is associated with higher achievement (Košir & Tement, 2013; Malecki & Demaray, 2006), and can have a moderating effect contributing to the success of students from disadvantaged backgrounds (Becker & Luther, 2002).

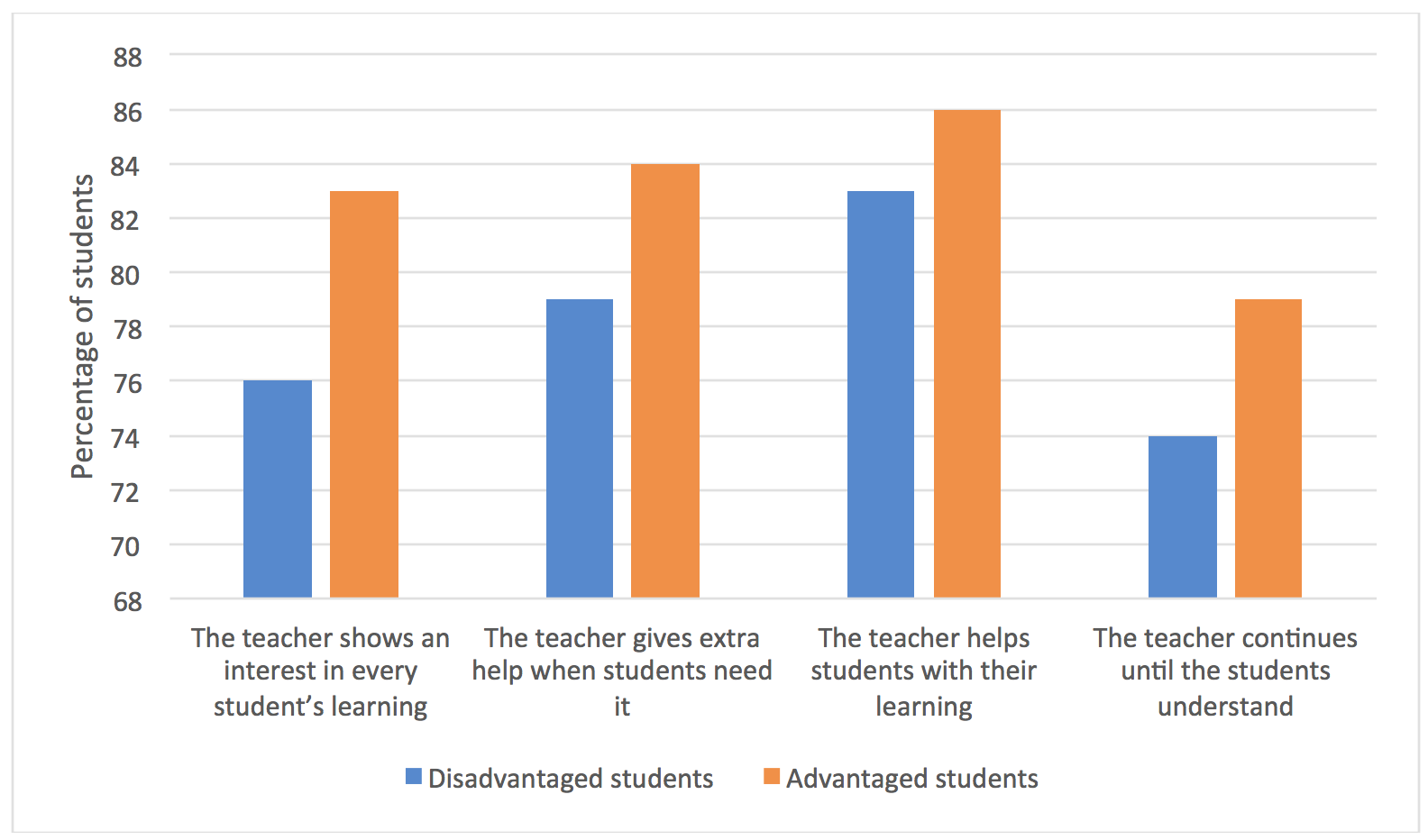

PISA investigated student perceptions about the extent of the support they receive from their English teachers (or language of instruction teachers in non-English speaking countries). Teacher support was measured by asking students how frequently the following behaviours occurred (every class, most classes, some classes, never or hardly ever) in their English classes:

- The teacher shows an interest in every student's learning.

- The teacher gives extra help when students need it.

- The teacher helps students with their learning.

- The teacher continues until the students understand.

On average, Australian students were generally very positive about their teachers. Australian students reported an aggregate score on the teacher support index that, while lower than that of students in the UK, was similar to that of students in New Zealand, Singapore and Finland, and higher than that in the United States, Ireland and most of the East Asian countries.

However, students in disadvantaged schools did not report the same level of perceived support from their teachers as did students in advantaged schools (Figure 1). The largest difference lay in students' perceptions that the teacher shows an interest in every student's learning, with positive (every class, most classes) responses given by 76 per cent of disadvantaged students and 83 per cent of advantaged students. For each of the other teacher support items, there was about a five-percentage point difference between the proportion of advantaged and disadvantaged students who said the behaviours occurred in most or every English class.

Figure 1. Levels of perceived teacher support by student socioeconomic background

Teacher feedback

Teacher feedback is also critical to students' success. Teacher feedback is an essential part of the learning process that provides students with information about their performance or understanding (Hattie & Timperley, 2007). Feedback is associated with stronger performance and higher levels of motivation (Hattie, 2009).

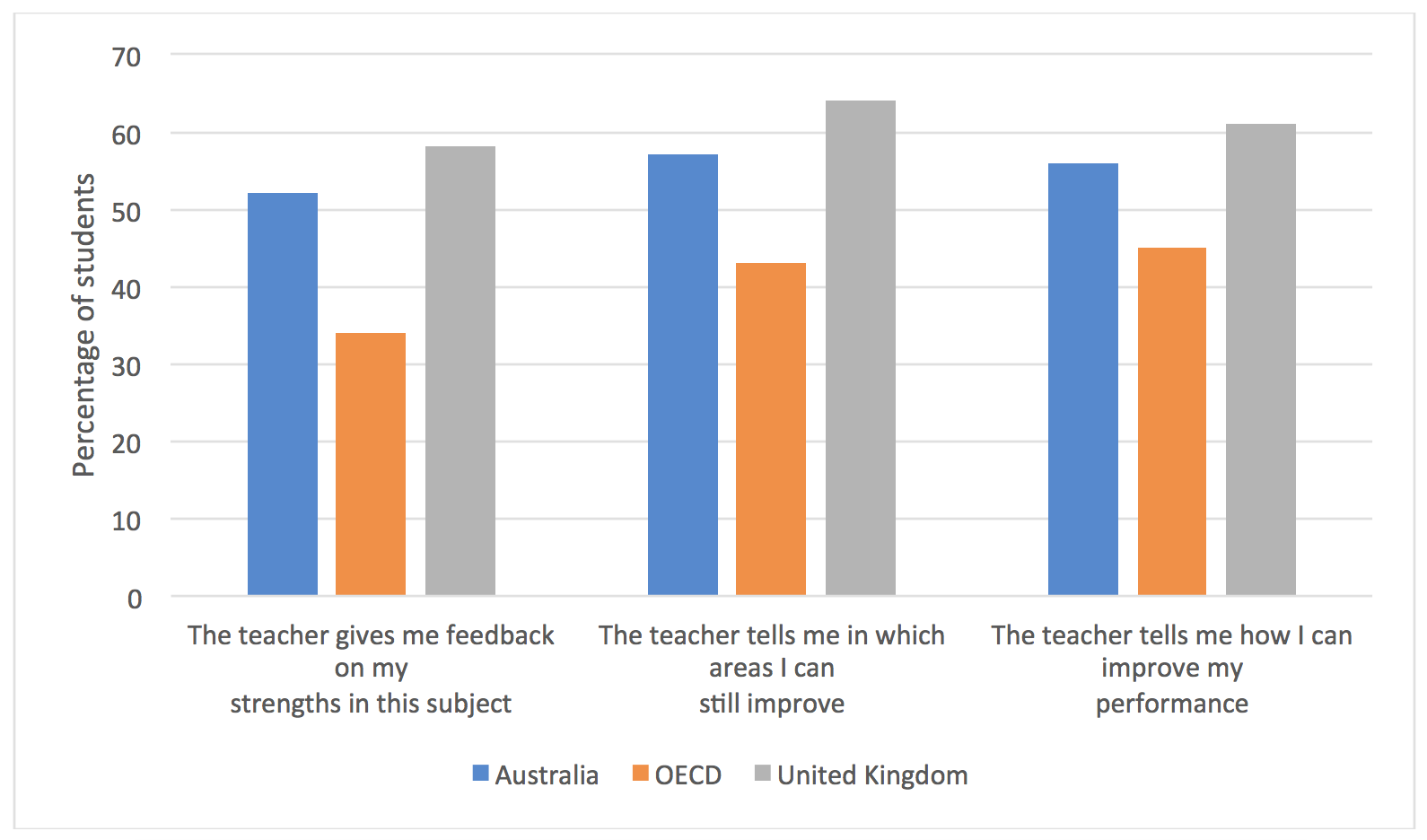

Teacher feedback was measured in PISA by asking students how frequently (every class or almost every class, many classes, some classes, never or almost never) the following behaviours occurred in their English/language of instruction classes:

- The teacher gives me feedback on my strengths in this subject.

- The teacher tells me in which areas I can still improve.

- The teacher tells me how I can improve my performance.

While Australia's score on the teacher feedback index was much higher than the OECD average and that of Japan, Finland and Ireland, among many, it was significantly lower than the average score in the United Kingdom, New Zealand and Singapore. Figure 2 shows students' positive (every class, most classes) responses to the three teacher feedback items for Australia, the OECD average and the United Kingdom, which achieved the highest score on the teacher feedback index among OECD countries.

Figure 2. Levels of perceived teacher feedback: Australia, United Kingdom and OECD average

Australian teachers seem to be perceived to be relatively good at telling students how they can improve their performance, as the difference between teachers in Australia and the UK is smaller on this measure than on the other items in the scale.

Interestingly, there were some gender differences on this scale, with male students reporting higher levels of feedback than female students. The explanation for this extra support likely rests in the fact that students were asked to report the frequency of teacher feedback received in English classes, a subject in which, traditionally, females significantly and substantially outperform males.

While the differences were fairly minimal on the teacher gives me feedback on my strengths in this subject (50 per cent of females and 53 per cent of males said this happened in most or every English class), they were larger for the teacher tells me in which areas I can still improve (54 per cent of females and 60 per cent of males) or for the teacher tells me how I can improve my performance (53 per cent of females and 59 per cent of males).

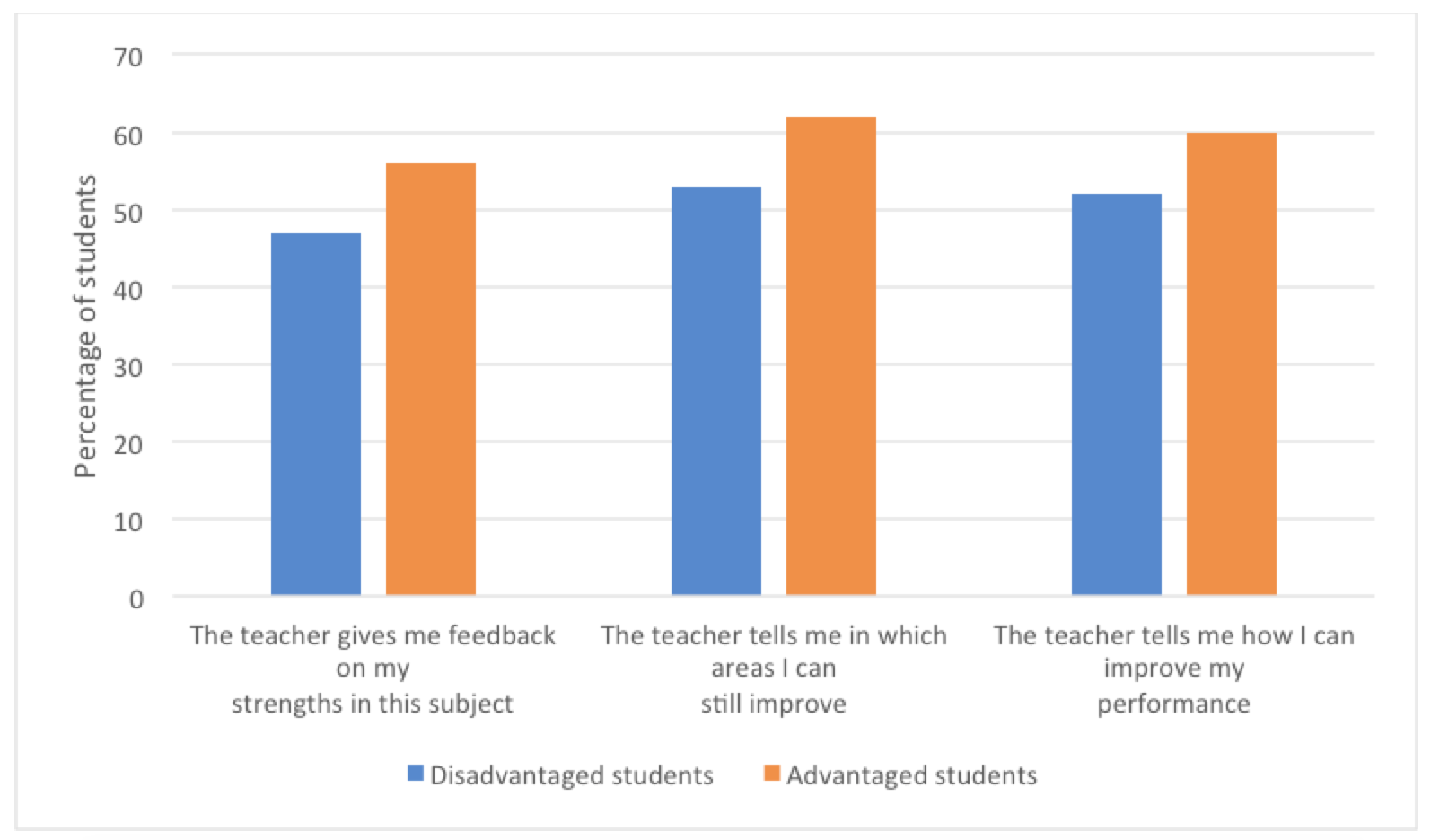

The logic of higher levels of teacher feedback being reported by groups with lower achievement fails, though, when examining the differences between Australia's socioeconomic groups. Instead, far more support is perceived to be offered to students in the advantaged group, which would in effect boost their already substantially higher performance (Figure 3). The differences between socioeconomic groups, which ranged from 8 to 9 per cent, were substantially larger than the gender differences (3 to 6 per cent).

Figure 3. Levels of perceived teacher feedback by student socioeconomic background.

Conclusions

Whilst, overall, the level of support and feedback provided to Australian students from teachers is generally good, the findings from this report that disadvantaged students perceive lower levels of support and feedback compared to advantaged students is very concerning.

The large achievement gaps (approximately three years of schooling) between students from advantaged and disadvantaged socioeconomic groups will only ever be breached if extra support is provided to those who really need it.

With disruptions to the 2020 school year likely to have a stronger negative impact on disadvantaged students, providing increased support for these students is more critical than ever before.

References

Becker, B. E., & Luthar, S. S. (2002). Social-emotional factors affecting achievement outcomes among disadvantaged students: Closing the achievement gap. Educational Psychologist, 37(4), 197–214.

Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. Routledge.

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 811–12

Košir, K. & Tement, S. (2013). Teacher-student relationship and academic achievement: a cross-lagged longitudinal study on three different age groups. European Journal of Psychology of Education. 29(3), 409–428.

Malecki, C., & Demaray, M. (2006). Social support as a buffer in the relationship between socioeconomic status and academic performance. School Psychology Quarterly. 21(4), 375–395.