What PISA tells us about our preparedness for remote learning

Within just a few weeks, the nature of teaching and learning has been flipped, nationally and internationally. The COVID-19 crisis has propelled schools to an online learning environment, to ways of teaching and learning that we were only just experimenting with until now. How do we make the most of this crisis?

The degree to which we are able to move forward, embrace change and capitalise on the strengths of both the old system and the new depends to an extent on our understanding of how well-prepared we are for this change. Data from the OECD's 2018 Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) and 2018 Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) can help shed light on students', teachers' and schools' preparedness for the ‘new normal'.

However it is important to recognise that some children will thrive and adapt easily to the new learning environment, that some children and schools are more prepared for this, and that for some children, this will serve to further amplify their learning disadvantage.

Preliminary findings from the Gonski Institute's Growing up digital Australia project confirm that ‘teachers and principals see family poverty as a key factor in accessing technology that students need for learning'. Research from the Smith Family found that while some 87 per cent of Australians can access the internet at home, only 68 per cent of Australian children living in disadvantaged communities have internet access at home, compared to 91 per cent of students living in advantaged communities. So what does this mean for students when remote learning is no longer an alternative but the only way to learn?

The home learning environment

PISA 2018 provides us with a wealth of evidence about how well our 15-year-old students are prepared for the sudden change from an environment in which they did most of their work at school and perhaps a few hours a day at home, to an environment in which they do all of their work at home – perhaps under the supervision of a parent, perhaps not.

Those of us who have suddenly turned into home workers will understand some of the issues involved, but having parents working from home at the same time as students are learning at home brings with it added layers of problems. For example, do they have a quiet place in which to study?

Eighty-eight per cent of Australian students in PISA 2018 reported that they did have a quiet place to study. This average, however, masks substantial differences between the haves and the have nots, which PISA measures based on parents' highest occupation and education level, and an index of home possessions comprising family wealth, cultural resources, and access to educational and cultural resources and books in the home.

Breaking down this statistic reveals that 78 per cent of disadvantaged students – those in the lowest socioeconomic quartile – report having a quiet place to study, compared to 96 per cent of advantaged students – those in the highest socioeconomic quartile. Similarly, 84 per cent of disadvantaged students, compared to 99 per cent of advantaged students, report that they have a computer at home to use for school work.

However, situations like this pandemic put enormous pressure on resources and these figures do not take into account whether students have parents also working from home, or other siblings also doing schooling at home. Just 41 per cent of students from disadvantaged families reported having three or more computers in the home, compared to 91 per cent of students in advantaged homes. This puts extra strain on disadvantaged students to negotiate for computer time.

Of course technology for learning is only as good as its use – whether students and teachers have the skills to use it and whether they do in fact use it.

Student readiness for online learning

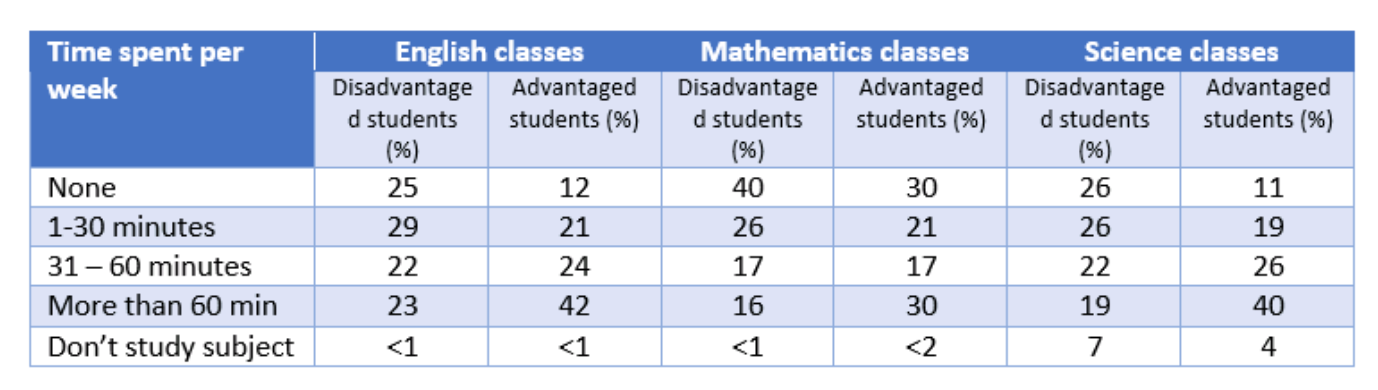

PISA 2018 asked students about the amount of time spent using digital devices during classroom lessons in a typical school week. This is summarised in Table 1 for English, mathematics and science classes (as the main foci of the cognitive assessment of PISA). Clearly, in each subject area, socioeconomically advantaged students have an edge over disadvantaged students in that they have many more hours of use under their belt, and so are more familiar with the software being used.

Table 1. Time using digital devices in English, mathematics and science classes per week, for disadvantaged and advantaged students, Australia (Source: PISA 2018)

In addition to familiarity with technology, if students are to be able to learn on their own, they also need to be able to set their own learning goals, to self-regulate and monitor their own learning. Teachers need to be developing skills using sustained projects, scaffolding students' learning and growth of self-regulation.

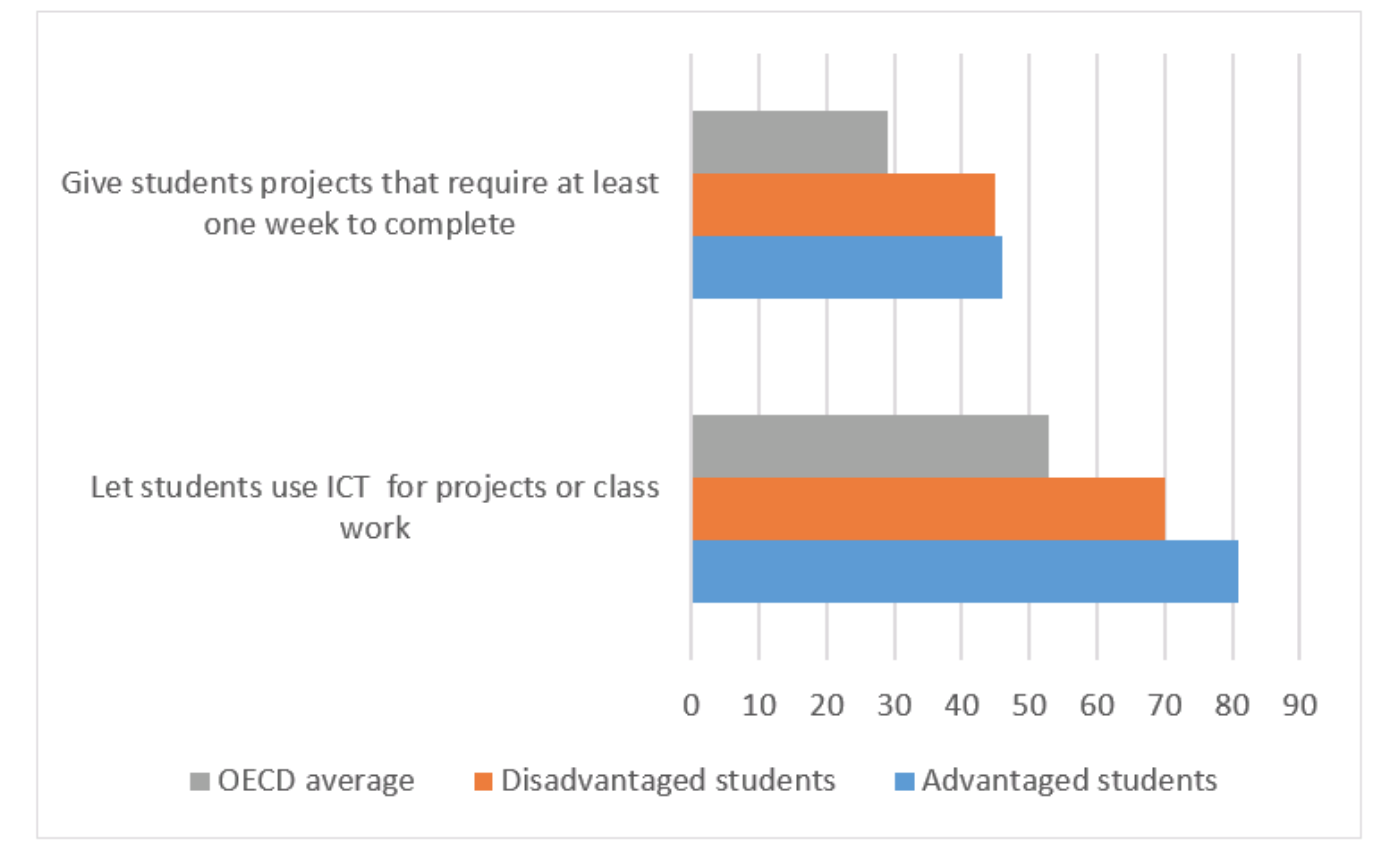

TALIS 2018 asked lower secondary teachers about the extent to which they used specific cognitive activation strategies in their classroom, and of relevance here are the enhanced activities: letting students use ICT for projects or classwork, and giving students projects that require at least one week to complete. This is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Use of enhanced activities, OECD average and Australia (Source: TALIS 2018)

In both activities, Australian teachers are performing at a higher level than across the OECD, on average. In Australia, just over 80 per cent of teachers at advantaged schools, compared to 70 per cent of teachers at disadvantaged schools, allow their students to use ICT for classwork or projects. This means that there are 30 per cent of teachers in disadvantaged schools and 20 per cent of teachers in advantaged schools not using technology in school on a regular basis.

More of a concern is that less than half of Australian teachers reported using sustained project work on a regular basis. While it is encouraging that there were no socioeconomic differences on this item, clearly not enough students are getting the experience they will need to help them regulate their own learning.

Teacher and school readiness for online learning

PISA 2018 also asked school principals the extent to which they agreed that teachers in their school have the necessary technical and pedagogical skills to integrate digital devices in instruction. Sixty per cent of disadvantaged students and 74 per cent of advantaged students attended schools in which the principal agreed or strongly agreed that this was the case. The picture is slightly brighter in terms of the availability of effective professional resources for teachers to learn how to use digital devices: 67 per cent of disadvantaged students and 78 per cent of advantaged students attended schools in which principals agreed or strongly agreed this was the case.

TALIS 2018, meanwhile, asked teachers about their participation in professional networks and online courses and seminars. In the 12 months prior to TALIS 2018, about three-quarters of teachers at disadvantaged schools (76 per cent) and 69 per cent of teachers in advantaged schools had participated in online courses or seminars. Fewer teachers indicated that they were part of a professional network – 64 per cent of those in disadvantaged schools and 59 per cent of those in advantaged schools.

The status of teaching

This current crisis provides an opportunity for teachers to shine, to show that they can ensure that students stay connected and engaged with their learning in a time of great upheaval.

We know from TALIS that the majority of teachers in our schools are open to innovation and most say they strive to develop new ways of teaching and learning. We also know the vast majority of teachers enter the profession in order to ‘influence the development of children and young people' (96% of teachers), or ‘to provide a contribution to society' (93 per cent of teachers), so it must be a source of stress to many that teaching is not a profession of high prestige in Australia. Indeed, just 45 per cent of Australian teachers agreed or strongly agreed that the teaching profession is valued in society (Fig II.2.1).

Across the world, though, people are suddenly realising how important teachers are. Many are gaining a new appreciation of the complexity of the task of teaching and of the professional relationships that teachers develop with their students. Only time will tell if this crisis will lead to an improvement in teachers' social status.